Some weeks ago James Bach began a series on Quality is dead. Since up to now he did not yet write up more of it, I get in touch with him via instant messaging. He explained to me that quality is dead, it cannot be brought back to live. How come?

Continue reading Testing quality into the productCategory Archives: Testing

Software Testing

Call for peer reviews

In October I’ll have a session at the Agile Testing Days in Berlin. So far I have prepared an article, which has gone through two iterations of review already. Today I decided to seek more review comments on it before making it final. If you think you can help me and have some time to spare for a 10 page document, please drop me a line at shino at shino.de. Thanks in advance.

Cowboy Testing vs. The Cash Cow

Over the past week I was contacted by two persons, who described to me that their current employee was not doing any software testing activities at all before they joined the company. Ok, you might say, how many years or decades have past since then? Two years in one case and the other one is from this year. What? We have 2009, over 50 years ago software testing was coined interalia by Jerry Weinberg, and there are companies out there, who do not do software testing at all? Yes, this seems to be true. In addition I have a name for this: Cowboy Testing. What? I thought they’re not testing at all? Of course, professional software programmers who built the software are going to “try out” what they built. According to the case studies, these programmers were not using test-driven development, or automated testing, or even continuous integration, but there was some kind of testing like activity included into the software before shipment, otherwise these companies will truly run out of business.

Pradeep Soundararajan just blogged today about the Software Testing cash cow. This is the opposite side of todays testing activities. Companies go out and pay other companies for the lacks of their testing process. These companies do not seem to think about the outcome of their actions, since they get scammed by billed hours for extensive documentation and promises from the testing companies.

Personally I am glad to work in the middle of these two extrema. My company feels responsible for the quality of their work and knows that quality needs to be considered from the beginning of the project. Still, there are improvements possible. Basically I am a protagonist of test-driven development and try to introduce colleagues to it using Coding Dojos and Prepared Katas – with little to no success so far. There is still some more work left to do, i.e. in understanding The Composition Fallacy or Acceptance Testing using frameworks like FitNesse. But at least my company noticed the fact that we need to test our products and that this needs to be done by employed people within the company itself. Amen.

Some links from the week

Ben Simo explains his view on Best practices related to the first two principles of the Context-driven school of testing and makes a fantastic conclusion:

No process should replace human intelligence. Let process guide you when it applies. Don’t let a process make decisions for you.

Seek out continuous improvement. Don’t let process become a rut.

Process is best used as a map; not as an auto-pilot.

Matt Heusser came up with some thoughts regarding failing Agile teams. Indeed some time ago Alistair Cockburn already discussed this topic in more detail. I found both quite worth reading.

Developer-tester, Tester-developer

During this week I watched the following conversion between Robert C. Martin and Michael Bolton on Twitter:

Uncle Bob

@dwhelan: If you’ve enough testers you can afford to automate the functional tests. If you don’t have enough, you can’t afford not to.Michael Bolton

Actually, it’s “if you have enough programmers you can afford to automate functional tests.” Why should /testers/ do THAT?Uncle Bob

because testers want to be test writers, not test executers.Michael Bolton

Testers don’t mind being test executors when it’s not boring, worthless work that machines should do. BUT testers get frustrated when they’re blocked because the some of the programmer’s critical thinking work was left undone.Uncle Bob

if programmers did all the critical thinking, no testers would be required. testers should specifying at the front and exploring all through; not repeating execution at the end.Michael Bolton

I’m not suggesting that programmers do all the critical thinking, since programmers don’t all of the project work. I am suggesting, however, that programmers could do more critical thinking about their own work (same for all of us). Testers can help with specification, but I think specification needs to come from a) those who want and b) those who build.

Over the weekend I thought through the reasoning. First of all I truly believe that both are right. Elisabeth Hendrickson stated this in the following way:

In any argument between two clueful people about The Right Way, I usually find that both are right.

Truly, both Uncle Bob and Michael Bob are two clueful people. In the conversation above they seem to be discussing about The Right Way, and I believe they are both right – to some degree, in some context, depending on the context. Basically this is how I got introduced to the context-driven school of testing.

The clueful thing I realized this morning was my personal struggle. Some months ago I struggled whether I am a tester-developer or a developer-tester. Again raising this point in my head with the conversation between a respected developer and a respected tester opened my eyes. Three years ago I started as a software tester at my current company. Fresh from university I was introduced into the testing department starting with developing automated tests based on shell-scripts. Finally I mastered this piece and got appointed to a leadership position about one and a half years later. Until that point I thought testing was mostly about stressing out the product using some automated scripts. Then I crossed “Lessons Learned in Software Testing” and got taught a complete new way to view software testing.

The discussion among these two experts in their field raised the point of my personal struggle. Testing is more than just writing automated scripts. Over and over executing the same tests again is a job a student can do. It’s not very thought-provoking and it gets boring. Honestly, I haven’t received a diploma in computer science (with a major in robotics) to stop thinking at my job. Therefore I got into development topics. Since our product doesn’t include good ways for exploratory testing, I came up with better test automation. Basically the tools I invented for the automated tests also aid in my quest to be good as an exploratory tester.

So what was I struggling with? Basically I realized that on my job the programmers get all the Kudos. That’s why I started investing time in becoming a better programmer. Meanwhile I found out that it’s also a fun thing to do. You can see the results whenever you run your programs. This is why I never gave up looking at code, dealing with it. Sure, it’s not what Michael Bolton or Jerry Weinberg mean with software testing. On the other hand it’s what I would like to do.

Basically I consider myself a developer for software test autmation. I have a background in software development and I have an understanding of software testing. (I leave it up to my clients and superiors whether I’m a good one or not.) In the way I understand my profession it’s necessary for me to know about both sides. This is also why I now realized that I am a tester-developer, not a developer-tester. As I just realized my personal struggle comes from the aspect that I am not sure, whether I really ever was a software tester or not. But for sure I have started to become a developer.

In order to conclude this posting with the initial discussion from the two experts in their fields, there is one thing left to say. As a software tester you may choose to become a developer of test automation. Robert Martin refers to these kinds of testers. On the other hand as a software tester you may choose to become a tester who applies critical thining. Michael Bolton refers to these kinds of testers. Whether or not to choose one path over the other may be up to you.

Testability vs. Wtf’s per minute

Lately two postings on my feed reader popped up regarding testability. While reading through Michael Boltons Testability entry, I noticed that his list is a very good one regarding testability. The problem with testability from my perspective is the little attendance it seems to get. Over the last week I was inspecting some legacy code. Legacy is meant here in the sense that Michael Feather’s pointed it out in his book “Working effectively with Legacy Code”: Code without tests. Today I did a code review and was upset about the classes I had to inspect. After even five classes I was completely upset and gave up. In the design of the classes I saw large to huge methods, dealing with each other, moving around instances of classes, where no clear repsonsibility was assigned to, variables in places, where one wouldn’t look for them, etc. While I am currently reading through Clean Code from the ObjectMentors, this makes me really upset. Not only after even ten years of test-driven development there is a lack of understanding about this practice, also there is a lack of understanding about testability. What worth is a class, that talks to three hard-coded classes during construction time? How can one get this beast under test? Dependency Injection techniques, Design Principles and all the like were completely absent on these classes. Clearly, this code is not testable – at least to 80% regarding the code coverage analysis I ran after I was able to add some basic unittests, where I could. Code lacking testability often also lacks some other problems. This is where Michael Bolton, James Bach and Bret Pettichord will turn in heuristics and checklists, the refactoring world named these as Smells.

On the Google Testing blog was an entry regarding a common problem, I also ran into several times: Why are we embarrassed to admit that we don’t know how to write tests? Based on my experience project managers and developers think that testers know the answers for all the problems hiding in the software. We get asked, “Can you test this?”, “Until when are you going to be finished?” without a clear understanding of what “tested” means or any insight what we do most of the time. “Perfect Software – and other illusions about testing” is a book from Jerry Weinberg from last year, which I still need to read through in order to know if it’s the right book to spread at my company – but I think so. If a develoepr doesn’t know about the latest or oldest or most spread technology, it’s not a problem at all. If a tester does not know how to “test” this piece of code, it is. He’s blocking the project, making it impossible to deliver on schedule – escalation! What Misko points out in his blog entry is, that the real problem behind this is also testability:

Everyone is in search of some magic test framework, technology, the know-how, which will solve the testing woes. Well I have news for you: there is no such thing. The secret in tests is in writing testable code, not in knowing some magic on testing side. And it certainly is not in some company which will sell you some test automation framework. Let me make this super clear: The secret in testing is in writing testable-code! You need to go after your developers not your test-organization.

I’d like to print this out and hang it all over the place at work.

Overview of Agile Testing

In the just released July issue of the Software Test and Performance Magazine there is an article from Matt Heusser, my mentor in the Miagi-Do School of Software testing, and Chris McMahon introducing to the most basic terms surrounding Agile Testing. Before they both wrote them down, I was able to provide some feedback on it. It seems to be enough feedback to get a mentioning at the end of the article. Basically I’m pleased to be able to provide my help.

Since I mentioned the Miagi-Do School, I have to make clear that the term school is not meant in the Kuhnian way. James Bach pointed out to me that he uses the term school regarding the five schools of software testing (Analytic, Standard, Quality, Context-driven and Agile) as a school of thought in such a way. This means that to adapt a mindset. Like James put me out, there are few circumstances where being driven by the context is contra-productive and made me think about three such situations. By the way: Can you think of three situations where being driven by the context of the situation is unnecessary?

From my understanding that I got from Matt’s Miagi-Do school it is not to be understood in the Kuhnian way.

Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should

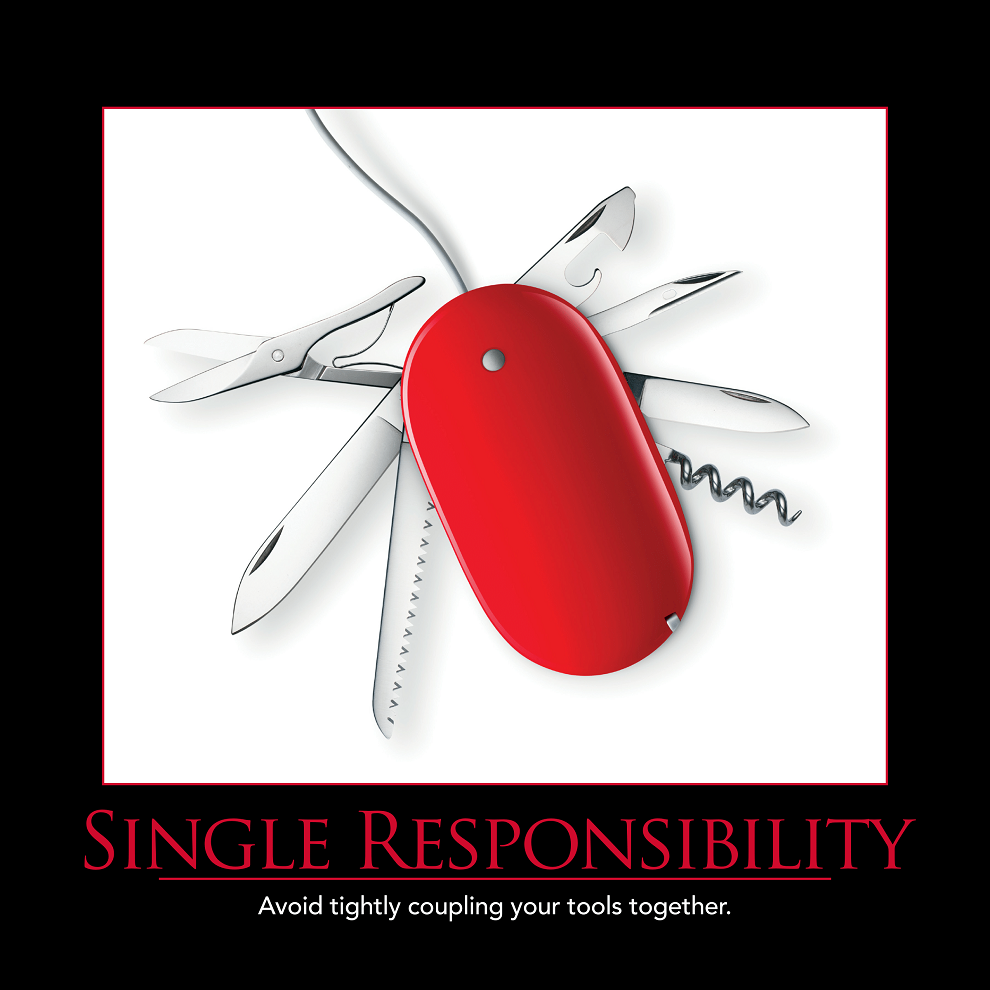

The following I got from a post on design principles related to object oriented code. You can find the whole enchilada here.

Today I was surprised that – while the principle of single responsibility is rather new in the software world – this principle is known for a long, long time in the testing world. Why?

On the project I’m currently working on we got our requirements as an database dump. Our developers decided to generate the configuration – our system under test – using some scripts, extracting it from the database directly and transforming it into the configuration for the software that we will deliver.

The test team that was asked to do the test automation for this configuration then was asked to built some automated tests for use in FitNesse. What they now did was to do pretty much the same as our development and have the test cases generated from the database. This may sound like a reasonable approach.

So, where’s the problem? The problem is that the resulting tests are not aware of the context. What is the context? The context is, that we need to deliver some rating software to a customer in Brasil. The tax system in Brasil is divided by the 27 states. We have four major bunches of baselines, each with about 8 to 10 variations in the baseline price (20, 40, …). The resulting configuration consists of about 4 times 10 times 27 (= 1080) different single variations. For each single variation there are about 20 to 100 single test cases necessary. The generated test suite now consists of a major bunch of tests (> 100000), which run on an overall system level against our delivered system with a test execution time of about 45 seconds. This results in an exhaustive regression test suite which takes 24 hours to execute. Due to the payload generated the FitNesse system is not handling these tests in a stable way, causing some crashes due to the amount of test cases in the overall structure.

So, restating the situation from a different perspective: The configuration gets generated and adaptation to changing requirements just takes a few hours for the developers. Test case execution is near to be impossible. On the other hand there are high test maintenance costs attached to the tests generated resulting in a high amount of rework necessary to keep up with the development team. Delivering feedback quickly to the developers is unlikely to happen. So, what’s the reason to have this high amount of never executed test cases in first place?

This is where I get to the topic of this post: Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. Just because it is possible to generate an exhaustive test suite for test automation, does not mean you should do this. When the resulting test execution times perform badly and even cause the test system to crash once in a while due to the high amount of tests included, you should refuse to do so.

So what should I do? Clarify your mission for the testing activities. What is the goal of your testing? Do you want to find risky problems quickyl? Then find another approach. Do you want to prove that everything is fine ignoring the approach of the development team? Then you should build an exhaustive test suite – probably. (I would suggest to look for a better approach to get feedback in 90 minutes maximum on it.) Know your context. How is the configuration generated? If errors reported by your test suite will be the same for all the different states, then you should re-think your approach. If there is a complex logic attached to generating the configuration, then probably you should consider testing that logic and just send out some tracer bulletts from end to end. What you can always do is to reconsider your current approach and check for opportunities to improve. The time that you might be able to win due to this, can be taken for follow-up testing and catching up in other activities. Maybe you can spend some more time pairing with your developers on the unit tests?

Testing in the days of Software Craftsmanship

Matt Heusser came up with the idea of the Boutique Tester. While reading through his article, I was wondering about the same striking question that arises in me since the early days of the Software Craftsmanship movement: Where are testers going to be in the Craftsman world?

Some months ago I started a series which I called Testing focus of Software Craftsmanship, covering Values, Principles I and Principles II and in addition I have planned an entry on Principles III, that I did not conclude so far. Most of the stuff in it I took from Elisabeth Hendrickson, Lisa Crispin, Janet Gregory, Brian Marick, James Bach, etc., etc. In this series I tried to raise an understanding of the testers role in the craft world while just restating the lessons most Agile teams already learned. The reason that I did not yet conclude this series is that I came to the realization that there seems to be no clear understanding of the sticky minded in the craftsman worldview for me.

Reflecting back on the lessons I learned from Agile methodologies like extreme Programming, Scrum, Crystal or Lean I remember myself being a bit jealous. Programmers were taught to use test-driven development, pair programming, big visible charts, planning poker. For me they seemed to have most of the fun. The tester simply does testing – the stuff they always do. As long as they don’t get into the way, this is wonderful… It was striking first, but when I realized that there are definitions of Exploratory Testing, Pair Testing, Retrospectives, etc., I got aware that testers also have fun activities.

A while back I proposed to rename the Agile testing school to the example-driven one. After getting some feedback from peers, I realized that there seem to be no room for school-mindsets in the Agile world and care for naming in the other schools. My initial motivation to rename the Agile school was driven by the realization that the Agile view on testing seem to be a good one for craftsmanship either. While my reasoning was based on poor assumptions, I started to realize a bigger argument behind this.

The bigger argument behind all three previously described situations is from my point of view that Software Testers have defined their craft long, long ago. Jerry Weinberg wrote in December about the way unit testing was done in the older days. Over the years there have been several thought-leaders appeared for Software testing. (I refuse to name a few here, since I know I’m too few in business to give honor the right ones.) Over and over the craft of software testing has been discussed, defined and found anew as the latest approaches to Agile testing teaches us. Just a few months back there was a heavy discussion on why Agile testers just define the terms that context-driven testers already teach since decades.

What is the difference between Software Craftspersons and Testing Craftspersons then? Testers know their craft from decades of experiencing and definition. There are more than enough books out there that teach good software testing just as not so good techniques. Software testers have most of their set of tools together to start leading their craft. For the development world this is not as true. Over the decades programming languages have come up and fallen down. Programming techniques like assembler, structured programming languages, logical programming languages, object-oriented programming languages, functional languages. The craft of software development seems to be more fluent to me as the craft of software testing. You can nearly apply all the testing techniques found in the books to your software, even to real world products as an Easy Button.

My point is that Matt raises a good point in his Boutique Tester article. Testers can directly go out and provide their testing services, gaining experiences over the years in order to improve. Maybe they can also take apprentices to teach the lessons they learned over the years. Basically I assume his proposal could work, though I’m concerned whether I would like to view myself more as a tester-developer or more as a developer-tester. In the end I think what matters most, is that there is only us and testers and developers form some kind of a symbiosis, just as automated and manual testing does. It’s a good thing that we’re not all generalists, but we should keep our mind open for different views of the problem at hand to compose an improved solution to it.

Three stone cutters

Ivan Sanchez put up a blog entry on a parable: Three stone cutters. He challenged my thoughts with the following question:

Sometimes I have this feeling that we as professionals are frequently trying to be more like the [“I’m a great stone cutter. I can use all my techniques to produce the best shaped stone“] stone cutter than the [“I’m a stone cutter and I’m building a cathedral”] one. Am I the only one?

Due to the analgoy I felt the urge to reply to this question with Elisabeth Hendricksons Lost in Translation and Gojko Adzics Bridging the Communication Gap. Most of the stone cutters I meet in daily business think they are creating a cathedral, while building a tower of babel. The biggest obstacle to efficient project success lies from my point of view in communication among team members.

This principle was discovered in his research on successful project in the 90s and early 2000s by Alistair Cockburn, see for example Methodology Space or Software development as a Cooperative Game (Warning: don’t get lost on his wiki site just as I did several times). Software Development is done for people by people. Since people are strong on communicating and looking around, software development as whole should strengthen this particular facet of us. A cathedrale is of no use if the entrance is on the top of the highest tower. Though during day to day work I see software developers lacking early feedbacks, that do not see the problem.

The industry I’m working in has a high changing rate of requirements. In the mobile phone industry there really are impacts from competitors, that you will have to react on to stay in business. For me this means to reduce the time to market for the product we’re building as massive as reasonable from a quality perspective. This also means to communicate with our customers spread all over the world in different time zones – even in distributed teams. This means that I need to find technical and motivational ways to bring people together that do not see each other on a day to day basis in the office. Just last week I we performed a Lessons Learned workshop on one of our products, where our colleagues in Malaysia took there web cam the first time and showed us how the world was looking outside their office. (It was during a refreshening break, so don’t get wild on wasted resources, my dear boss.) This lead to personal touch and a lower personal distance between the two teams – at least during that session.

Anyways I wonder why these moments happen too little. Instead I see teams – erm basically groups of people – working without communicating with each other though they need some information from the co-worker directly near to them and wondering in the end why there is an integration problem. Another point is the problem of open interfaces (lacking communication of protocols and the like), open scope (lacking the communication of content of the project), open everything. Clearly, for me it seems there is no way to communicate too much, it’s more the opposite that I bother about.